Advertisement

BMC Medical Education volume 24, Article number: 1518 (2024)

Metrics details

Due to the complex and abstract anatomy of the nervous system, neurology has become a difficult subject for students of clinical disciplines. It is imperative to develop new teaching methods to improve students’ enthusiasm for learning this course. Small private online courses (SPOC) combined with problem based learning (PBL) blended teaching models based on massive open online course (MOOC) provides a new direction for future neurology teaching reform. This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of applying SPOC combined with PBL in neurology teaching.

This study was conducted during the 2020 intake of undergraduate students at the Second Hospital and Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University. A total of 48 students were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to either a Lecture-Based Learning (LBL) group or a SPOC + PBL group, with 24 participants in each group. After the classes, comparisons were made between the two groups in terms of teaching methods, increases in learning interest, level of participation in learning, satisfaction, and closed-book unit test scores.

The average unit test score of the SPOC + PBL group was 84.29 ± 1.65, the average score of LBL group was 77.0 ± 1.92. The difference in average scores between the two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.01). The proportion of students with 91–100 points in SPOC + PBL group was higher than that of LBL group, and the difference was statistically significant, P < 0.01. Student satisfaction survey in the SPOC + PBL group was significantly higher than that in the LBL group, P < 0.01.

The application of SPOC combined with PBL teaching based on MOOC in neurology teaching may be more effective than traditional LBL model. It is expected to help medical students overcome the “fear” of learning neurological diseases, improve the teaching effect of neurology courses, and meet the needs of modern medical education by employing a hybrid course structure and adopting a problem-oriented approach.

Peer Review reports

Neurology is an important second-level clinical discipline [1]. The localization and qualitative diagnosis of neurological diseases occupy a pivotal position in the teaching system of neurology, requiring students to have basic knowledge of nervous system anatomy [2]. However, the anatomy of the nervous system is inherently complex and abstract, and many students do not grasp it well in their basic medical studies. This has led to neurology becoming a difficult subject for students of various medical majors in clinical disciplines, and students lack enthusiasm for learning this course [3]. Therefore, it is imperative to develop new teaching methods. Small private online courses (SPOC) combined with problem based learning (PBL) blended teaching models based on massive open online course (MOOC) provides a new direction for future neurology teaching reform [4].

Neurology is a required course for fourth-year clinical students in medical colleges that encompasses a vast amount of content within limited class hours. For instance, a general introduction to the nervous system requires students to review neural anatomy beforehand, but the anatomy course is typically offered in the first year of college, which has been forgotten because of a long interval. Given the limited time available, it is impractical to review it again in class. In addition, the traditional Lecture-Based Learning (LBL) teaching model, where the teacher lectures on the stage while students listen below, not only affects the overall teaching progress, but also fails to highlight key and difficult points. The LBL model cannot meet students’ needs for autonomous learning, team communication and cooperation, or the ability to connect basic theoretical knowledge with clinical practice.

As a new Internet-based teaching model, MOOC has attracted much attention and promotion in Chinese university education, becoming an online course platform adopted by many higher education institutions. The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School of Lanzhou University fully opened up the MOOC in 2018, playing a significant role in the construction and operation of online open courses. From the perspective of learning resources, MOOC brings together high-quality course content from top universities and well-known experts around the world, providing learners with an extremely rich knowledge treasure trove. In terms of learning methods, MOOC has a high degree of flexibility. Learners can independently choose learning courses according to their own time arrangements and learning progress. However, with the advancement of the MOOC teaching model, it was found to have disadvantages such as students’ inability to communicate and ask questions with teachers on the spot, resulting in the teaching effect being less than ideal [5].

SPOC, a term first coined by Professor Armando Fox at the University of Berkeley in Fox, which implies an adaptation of MOOC to suit the specific needs of an educational body, diversification that obeys educational criteria tending to personalize learning. SPOC combines the openness and sharing of MOOC with teacher-student interaction in traditional classrooms, integrating the advantages of online and offline teaching [6].

At present, the PBL teaching method is widely used in neurology [7,8,9,10], which is a student-centered teaching model [11] that is helpful in cultivating students’ ability to explore problems, but it is not conducive to students’ mastery of basic knowledge [12] and lack of objective evaluation methods [8, 9, 13].

MOOC help update general knowledge and are directed to large groups, while SPOC allow the development of educational projects for specific communities, adjusting the contents to their needs. Based on this, we consider making innovative improvements to the teaching methods of neurology by applying SPOC combined with PBL model based on MOOC in the teaching of Neurology [14].

To explore the effectiveness of the application of SPOC combined with PBL model based on MOOC in the teaching of Neurology, we post pre-class content on nervous system anatomy on the Xuexitong online teaching platform to save time for review and preview, deliver offline lectures on various chapters of neurology during class, adopt the PBL approach to inspire students’ thinking and stimulate their interest in learning, and provide online answers and reinforcement of key and difficult points after class.

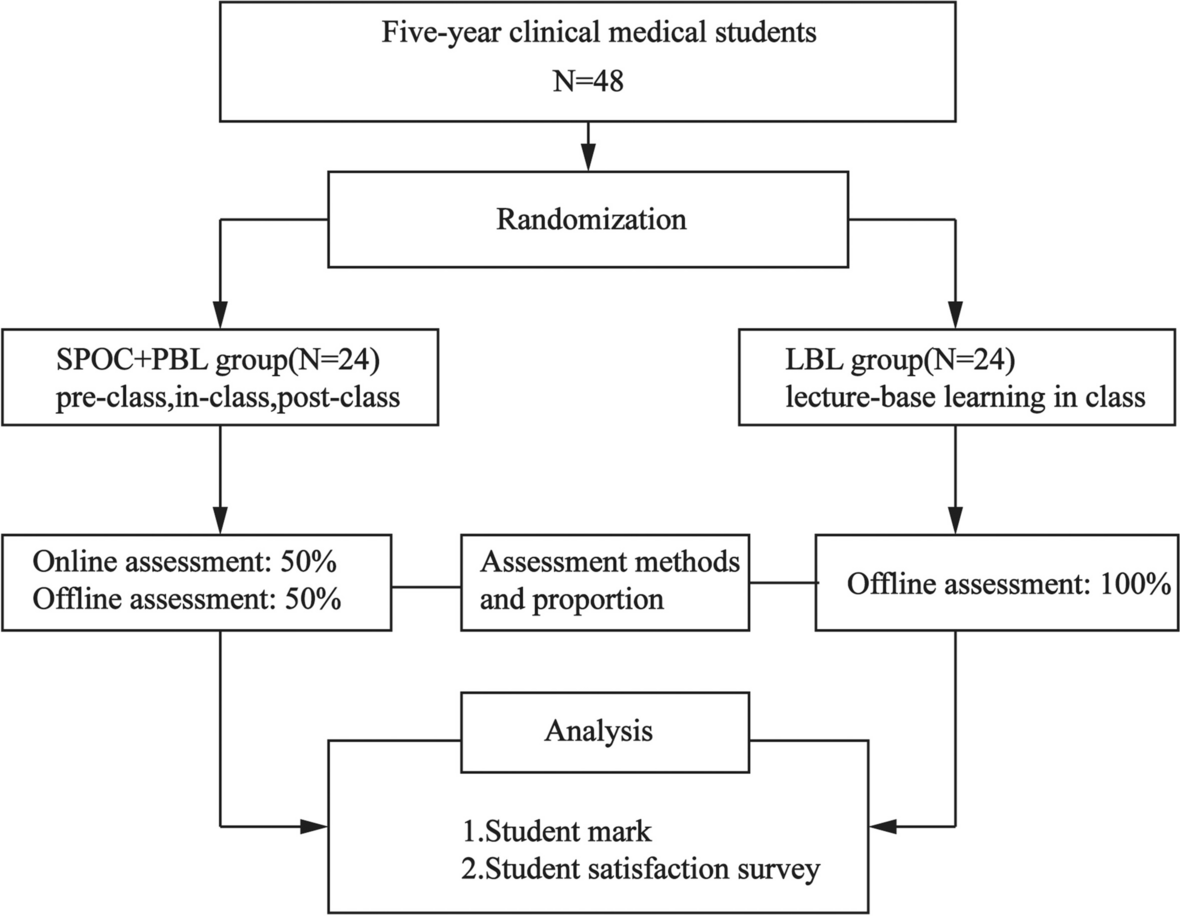

A total of 48 students were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to either the LBL or SPOC + PBL group, with 24 participants in each group. They were all fourth-year students majoring in five-year clinical medicine from the Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School of Lanzhou University. There was no statistically significant difference in the general information between the medical students of the two groups, indicating comparability. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT study flow diagram. To ensure that students of different academic levels are relatively evenly distributed in each research group, we considered multiple relevant factors including students’ previous course grades, comprehensive academic evaluations, and other aspects of information (Table 1).

CONSORT study flow diagrams

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital and Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University (2023A-817). All participants completed an informed consent form that included the purpose of the study before the start of the study.

A total of 48 participants were enrolled in this study. They were randomly divided into the LBL group (n = 24) and SPOC + PBL group (n = 24). The average ages of the LBL group were 20.71 ± 0.251 and SPOC + PBL group were 20.93 ± 0.324 years, respectively. There were 11 (45.83%) male and 13 (54.16%) female participants in the LBL group, in SPOC + PBL group were 12 (50.0%) male and 12 (50.0%) female participants.

The textbook we selected was the 8th edition of Neurology [15], and the content we taught was the second chapter, Anatomy, Physiology, and Localization Diagnosis of Nervous System Lesions. The content of the selected chapter was divided into four class hours, taught by the same group of well-trained and experienced teachers, primarily focusing on the teaching outline.

The LBL group focused on traditional teaching and notified students one week before class to preview the core content of this chapter. During the class, teachers mainly used the PowerPoint (PPT) to present the anatomical structure and localization diagnosis of the nervous system, interspersed with short videos, and posed questions to students.

The teaching process of the SPOC + PBL group was divided into three stages: before class, during class, and after class, and the specific process was shown in Fig. 2. Before class, teachers released preview materials on the learning platform, including PPT and flash GIFs of the anatomical structure of central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. Students can watch videos repeatedly, post difficult questions online, and complete their answers online after the teachers collect them. Completing the learning of this section before class not only laid a solid foundation for students to further understand the manifestations of nervous system lesions but also save more time for teachers to explain localization diagnosis in detail in later classroom teaching. During class, teachers adopt the PBL approach with students as the main body. This approach allowed students to fully understand the methods of localization diagnosis and then guided them in applying the knowledge from the textbook to solve practical problems. Specifically, it involved the following steps: (1) Teachers taught the methods of positioning diagnosis of lesions of the central nervous system, cranial nerve, and peripheral nerve through offline teaching; (2) Teachers prepared cases with typical neurological signs. Students were divided into groups to discuss and learn localization diagnosis, mastering the neurological signs of different lesion manifestations. Teachers provided answers to the questions raised by students in class on the spot; (3) Students completed in-class exercises online. After class, they completed the review and consolidation of difficult parts online, such as the manifestations and localization diagnosis of brainstem lesions. Teachers can also post homework assignments and extended reading materials.

SPOC + PBL teaching model

The LBL group adopted the traditional assessment method of the closed-book unit test (100%). The SPOC + PBL group adopted a diversified assessment and evaluation system, encompassing online previewing, interactive discussions, preview quizzes, classroom interactions, case analysis applications, and closed-book unit tests (Table 2). Since the SPOC + PBL group employed a hybrid teaching model consists of both online and offline scores, the final analysis of learning outcomes was conducted through a statistical analysis of the closed-book unit test scores from both groups.

To assess student satisfaction with the teaching methods, a survey questionnaire was introduced before they received their scores on the test. The questionnaire encompassed nine aspects: evaluation of teaching methods, increase in learning interest, enhancement of participation, improvement in learning initiatives, strengthening of team collaboration, advancement of information search abilities, promotion of clinical thinking and patient communication skills, and facilitation of teacher-student interaction. Based on the Likert scale method, the satisfaction evaluation in the questionnaire was divided into five levels: very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, slightly dissatisfied, and dissatisfied.

Data was collected and statistically analyzed using SPSS software version 25.0. Measurement data was expressed as (±S) for the t-test. Count data was expressed as n (%) using the chi-square test and rank-sum test (Mann–whitney U). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Graphics were created using the GraphPad Prism 9.5 software.

To ensure that students of different academic levels are relatively evenly distributed in each research group, we considered multiple relevant factors including students’ previous course grades, comprehensive academic evaluations, and other aspects of information. The results are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age, gender and course grades (P > 0.05).

To stimulate students’ interest in learning, encourage them to think independently, and enhance their ability to analyze and solve problems, ensuring effective learning outcomes, teachers reformed the assessment methods for the SPOC + PBL group. A diversified assessment and evaluation system was established, encompassing online previewing, interactive discussions, preview quizzes, classroom interactions, case analysis applications, and closed-book unit tests (Table 2). Online performance accounts for 50% of the total grade, whereas offline performance accounts for the remaining 50%, as shown in Fig. 3. The LBL group adopted the traditional assessment method of the closed-book unit test (100%). Since the SPOC + PBL group employed a hybrid teaching model, the final analysis of learning outcomes was conducted through a statistical analysis of the closed-book unit test scores from both groups.

The assessment methods for SPOC + PBL group

The average unit test score of the SPOC + PBL group was 84.29 ± 1.65, while in the LBL group, the average score was 77.0 ± 1.92, as shown in Fig. 4. The difference between the average scores of two groups was statistically significant (P < 0.01, effect size = 4.07, power = 1) (Fig. 4A, B). Among the students’ scores in the SPOC + PBL group, 51–60 points accounted for 0%, 61–70 points accounted for 8.33%, 71–80 points accounted for 20.83%, 81–90 points accounted for 54.16%, 91–100 points accounted for 16.67% (Fig. 4C). In the LBL group, 4.16% fell within the range–51–60 points, 16.67% were within 61–70 points, 25% scored 71–80 points, 50% got 81–90 points, and 4.16% achieved 91–100 points (Fig. 4D). The proportion of students scoring 91–100 points and 81–90 points in the SPOC + PBL group were higher than those in the LBL group (Table 3).

The unit test scores of LBL and SPOC + PBL groups. A–B Bar graph of the unit test scores of the LBL and SPOC + PBL groups. C Scatter plot of the unit test scores of LBL and SPOC + PBL groups. D Comparison of average scores between LBL and SPOC + PBL groups. **P < 0.01

A total of 48 satisfaction questionnaires were distributed for the survey in this study, and 48 valid questionnaires were returned with a valid recovery rate of 100%. The results (Fig. 5) indicated that students in the SPOC + PBL group were more satisfied with their teaching methods. Compared with the traditional LBL teaching method, the new teaching method can significantly enhance students’ interest and initiative in learning, improve learning participation, promote team collaboration ability, enhance teacher-student interaction, cultivate clinical thinking skills, etc. The results are presented in Table 4. The differences between the two groups were statistically significant (P < 0.05, effect size = 0.785, power = 0.997).

Satisfaction teaching level of LBL and SPOC + PBL groups

Neurology is highly specialized and difficult to understand, and is closely related to multiple basic medical disciplines, including anatomy, pathology, and diagnostics. The intersection and integration of these knowledge systems increases the difficulty of teaching neurology and also affects students’ enthusiasm for learning this subject [16,17,18]. Almost all chapters of neurology require students to review neural anatomy beforehand, but the anatomy course is typically offered in the first year of college and has been forgotten because of a long interval. Given the limited total class hours of this course, it is impractical to complete the review, learn new knowledge, and interact with students during class time [7]. Although the traditional LBL teaching model has unique advantages in classroom teaching [19, 20], the one-sided output of teachers makes students feel bored and unfocused. Teachers only completed the teaching task, were unable to fully understand the students’ grasp of the important and difficult points in each class, and were unable to guide students to analyze and solve problems independently [21]. In addition, it has entered the era of “knowledge explosion,” and traditional LBL teaching has been affected by time, space, and equipment, which can no longer meet current needs [22, 23]. MOOC is a large-scale open online course developed by Dave Cormier [24]. As the name suggests, all MOOC courses are openly accessible, not only online [25], but also in various flexible ways for students to acquire educational resources [26]. SPOC combines face-to-face classroom learning with online self-study, forming a sharp contrast with fully online MOOC [27]. It reintegrates the online and offline classrooms.

This study utilized the advantages of SPOC to divide the teaching process into three stages: before class, during class, and after class. The effective of a hybrid teaching model can fully utilize Internet resources, making it more diverse than traditional single-classroom teaching in the past. Before class, teachers will publish the learning objectives and tasks of each chapter on the learning platform, allowing students to specify and quantify the content of the chapter and clearly understand what they should learn and to what extent they should learn. Students were allowed to learn at their own pace. In addition, for basic medical knowledge that has been learned a long time ago, such as complex neuroanatomy and pathology, teachers can put all of them online in diverse forms, such as videos and 3D animation for students to review before class [28]. Students can repeatedly watch and post questions about the learning process online so that teachers can understand the problems existing in students’ learning.

In this study, the PBL teaching method was interspersed in the middle stage of an offline class. Due to sufficient preparation before class, students have laid a good foundation for the mastery of the important and difficult knowledge in the chapter, and teachers have enough time to teach and interact with students. Students discuss this in groups, and teachers can summarize or expand the relevant frontier knowledge points appropriately. After class, the teacher publishes homework that repeatedly emphasizes the important and difficult points in the chapter, then corrects the homework, and finally explains the answers online. This study employed a hybrid teaching model of SPOC and PBL, aiming to guide students to focus on understanding and applying knowledge and to promote teacher-student interaction and improve the utilization of time. M. Chi et.al reported that the flipped-classroom teaching mode based on a SPOC combined with PBL on nursing teaching can promote students’ abilities of autonomous learning, communication and cooperation, and clinical and critical thinking; improves their academic performance; and is recognized and welcomed by them [8]. Consistent with the results of M. Chi’s research, this study also showed that the teaching method of SPOC combined with PBL was significantly better than the traditional LBL teaching method in improving learning engagement, communication ability, and clinical thinking ability, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). In addition, this study has reformed the student assessment model, and the neurology course has used the traditional evaluation method, which is based on closed-book examination results. After the reform of SPOC combined with the PBL teaching model, diversified assessment methods were adopted, including online preview, interaction, and preview test accounting for 30%, and the unit test closed book score accounted for 50%. The mistaken belief of cramming for exams to pass was abandoned, and more attention was paid to students’ participation in learning and flexible use of knowledge. The results of the satisfaction survey showed that the satisfaction of the SPOC combined with PBL group was significantly higher than that of the traditional LBL group.

In this study, by comparing the written scores of unit tests between the two groups, it was found that the average score and the proportion of high-scoring students of SPOC + PBL group significantly higher than that of LBL group. Therefore, after the implementation of the teaching reform of SPOC and PBL, the academic performance of students can be significantly improved, the teaching effect is good, and teaching efficiency is also improved. The results of this study are consistent with those of other researchers [7]. This combined teaching method is helpful in improving students’ ability to combine theory and clinical practice and in improving the teaching effect. Meanwhile, students have overcome their “neural fear” in problem-based learning [29], cultivated good habits such as independent learning and literature review, and become more confident and willing to express their opinions. Through full interaction with students, teachers can discover their own problems, continuously improve their teaching methods, achieve self-growth, and enhance teaching quality. This is what is known as “teaching and learning benefit each other”.

At present, the PBL teaching method is widely used in neurology [7,8,9,10]. The main problem with the application of SPOC combined with the PBL teaching method is that teachers are required to fully prepare online video content and publish online interactive test questions. Since there is still a lack of unified syllabus to standardize online neuroanatomy teaching content, it takes a lot of time and effort for teachers to prepare online teaching content, whether it is to produce teaching videos or connect different Internet platforms. Therefore, for teachers, the application of SPOC combined with the PBL method in the teaching of neurology still needs to continuously accumulate experience and improve the process. For students, teachers also have higher expectations because the teaching method requires students to have strong self-learning and problem-solving skills.

This study is the initial stage of our research, focusing mainly on exploring the preliminary effects of the new teaching methods and practices, aiming to obtain an overall directional understanding and practical experience feedback. In the follow-up research, we will further enrich our research results and provide more comprehensive and valuable references for teaching practice. We will seriously consider organically combining PBL with SPOC or other teaching models, and further explore the impact of the synergistic effect of multiple teaching methods on students’ learning effects, so as to enrich our research results and provide more comprehensive and valuable references for teaching practice.

The application of SPOC combined with PBL teaching based on MOOC in neurology teaching may be more effective than traditional LBL model. It is expected to help medical students overcome the “fear” of learning neurological diseases, improve the teaching effect of neurology courses, and meet the needs of modern medical education by employing a hybrid course structure and adopting a problem-oriented approach.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Problem based learning

Lecture-Based Learning

Small private online courses

Massive Open Online Course

Han F, Zhang Y, Wang P, Wu D, Zhou LX, Ni J. Neurophobia among medical students and resident trainees in a tertiary comprehensive hospital in China. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):824.

Article Google Scholar

Merlin LR, Horak HA, Milligan TA, Kraakevik JA, Ali II. A competency-based longitudinal core curriculum in medical neuroscience. Neurology. 2014;83(5):456–62.

Article Google Scholar

Flanagan E, Walsh C, Tubridy N. ’Neurophobia’–attitudes of medical students and doctors in Ireland to neurological teaching. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(10):1109–12.

Article Google Scholar

Lin YS, Lai YH. Analysis of AI precision education strategy for small private online courses. Front Psychol. 2021;12:749629.

Article Google Scholar

Gleason KT, Commodore-Mensah Y, Wu AW, Kearns R, Pronovost P, Aboumatar H, et al. Massive open online course (MOOC) learning builds capacity and improves competence for patient safety among global learners: A prospective cohort study. Nurs Educ Today. 2021;104:104984.

Article Google Scholar

Bodagh N, Bloomfield J, Birch P, Ricketts W. Problem-based learning: a review. Br J Hosp Med (London, England : 2005). 2017;78(11):C167-c70.

Article Google Scholar

Kim YJ. The PBL teaching method in neurology education in the traditional Chinese medicine undergraduate students: An observational study. Medicine. 2023;102(39):e35143.

Article Google Scholar

Chi M, Wang N, Wu Q, Cheng M, Zhu C, Wang X, et al. Implementation of the flipped classroom combined with problem-based learning in a medical nursing course: a quasi-experimental design. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2022;10(12):2572.

Google Scholar

Hu X, Zhang H, Song Y, Wu C, Yang Q, Shi Z, et al. Implementation of flipped classroom combined with problem-based learning: an approach to promote learning about hyperthyroidism in the endocrinology internship. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):290.

Article Google Scholar

Vakani F, Jafri W, Ahmad A, Sonawalla A, Sheerani M. Task-based learning versus problem-oriented lecture in neurology continuing medical education. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(1):23–6.

Google Scholar

Arruzza E, Chau M, Kilgour A. Problem-based learning in medical radiation science education: a scoping review. Radiography (London, England : 1995). 2023;29(3):564–72.

Google Scholar

Bassir SH, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Amirikhorheh S, Karimbux NY. Problem-based learning in dental education: a systematic review of the literature. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(1):98–109.

Article Google Scholar

Jones RW. Problem-based learning: description, advantages, disadvantages, scenarios and facilitation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34(4):485–8.

Article Google Scholar

Feigin VL, Vos T, Nichols E, Owolabi MO, Carroll WM, Dichgans M, et al. The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):255–65.

Article Google Scholar

Jia JP, Chen SD. Neurology (8th Edition). Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2018. ISBN: 9787117266406.

Google Scholar

Lambea-Gil A, Saldaña-Inda I, Lamíquiz-Moneo I, Cisneros-Gimeno AI. Neurophobia among undergraduate medical students: a European experience beyond the Anglosphere. Rev Neurol. 2023;76(11):351–9.

Google Scholar

Ridsdale L, Massey R, Clark L. Preventing neurophobia in medical students, and so future doctors. Pract Neurol. 2007;7(2):116–23.

Google Scholar

Khatiban M, Falahan SN, Amini R, Farahanchi A, Soltanian A. Lecture-based versus problem-based learning in ethics education among nursing students. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(6):1753–64.

Article Google Scholar

Alhazmi A, Quadri MFA. Comparing case-based and lecture-based learning strategies for orthodontic case diagnosis: A randomized controlled trial. J Dent Educ. 2020;84(8):857–63.

Article Google Scholar

Faisal R, Bahadur S, Shinwari L. Problem-based learning in comparison with lecture-based learning among medical students. JPMA J Pakistan Med Assoc. 2016;66(6):650–3.

Google Scholar

Chan PP, Lee VWY, Yam JCS, Brelén ME, Chu WK, Wan KH, et al. Flipped Classroom Case Learning vs Traditional Lecture-Based Learning in Medical School Ophthalmology Education: A Randomized Trial. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2023;98(9):1053–61.

Article Google Scholar

Veit W. The evolution of knowledge during the Cambrian explosion. Behav Brain Sci. 2021;44: e174.

Article Google Scholar

Walsh K. The Cost Bubble in Medical Education: Will it Burst and When? Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2016;6(4):257–9.

Article Google Scholar

Maxwell WD, Fabel PH, Diaz V, Walkow JC, Kwiek NC, Kanchanaraksa S, et al. Massive open online courses in U.S. healthcare education: Practical considerations and lessons learned from implementation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(6):736–43.

Article Google Scholar

Hendriks RA, de Jong PGM, Admiraal WF, Reinders MEJ. Instructional design quality in medical Massive Open Online Courses for integration into campus education. Med Teach. 2020;42(2):156–63.

Article Google Scholar

Mahajan R, Gupta P, Singh T. Massive Open Online Courses: Concept and Implications. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56(6):489–95.

Article Google Scholar

Vaysse C, Chantalat E, Beyne-Rauzy O, Morineau L, Despas F, Bachaud JM, et al. The impact of a small private online course as a new approach to teaching oncology: development and evaluation. JMIR Med Educ. 2018;4(1):e6.

Article Google Scholar

Arantes M, Arantes J, Ferreira MA. Tools and resources for neuroanatomy education: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):94.

Article Google Scholar

Venter G, Lubbe JC, Bosman MC. Neurophobia: A Side Effect of Neuroanatomy Education? J Med Syst. 2022;46(12):99.

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Not applicable.

This study was supported by [the Course Construction of SPOC-driven Neurology Online/Offline Hybrid Teaching Mode-The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University] [Project No.: DELC-202305].

Xiaoling Li and Fanju Li contributed equally to this work.

Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

Xiaoling Li

Department of Neurology, The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University, No. 82, Cuyingmen, Chengguan District, Lanzhou, 730000, China

Fanju Li, Wei Liu, Qinfang Xie, Boyao Yuan, Lijuan Wang & Manxia Wang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

XLL, FJL, and MXW designed the study; XLL and FJL wrote the original manuscript; WL, QFX, and BYY collected the data; LJW and MXW analyzed the data; and all authors read and approved the final version.

Correspondence to Manxia Wang.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital and Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University (2023A-817). All participants completed an informed consent form that included the purpose of the study before the start of the study.

Not applicable.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

Li, X., Li, F., Liu, W. et al. Effectiveness of the application of small private online course combined with PBL model based on massive open online course in the teaching of neurology. BMC Med Educ 24, 1518 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06460-5

Download citation

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06460-5

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Advertisement

ISSN: 1472-6920

By using this website, you agree to our Terms and Conditions, Your US state privacy rights, Privacy statement and Cookies policy. Your privacy choices/Manage cookies we use in the preference centre.

© 2024 BioMed Central Ltd unless otherwise stated. Part of Springer Nature.